Look, we're losing circulation and advertising. The obvious answer is to destroy the product--

Look, we're losing circulation and advertising. The obvious answer is to destroy the product--If you care about journalism, your heart should be breaking about now.

We are all aware by now of the fall of the Knight-Ridder newspaper chain. It is being dismantled, thanks to Wall Street greed and the incredible ineptitude of Knight-Ridder management. The chain was bought by McClatchy, which actually is the best newspaper chain left in America. That would be the good news. The bad news is that McClatchy is selling off 12 of Knight-Ridder papers to fund the purchase, including my old paper, the

Philadelphia Inquirer. I was science writer at the

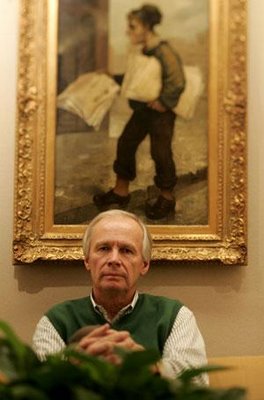

Inquirer from 1969 to 1980, the best job I ever had in journalism. In the last 20 years, Knight-Ridder emasculated what was arguably the best newspaper in America to keep the ass-holes on Wall Street happy. (I don’t like using profanity on this blog but I am at a loss to find another word. I’m really pissed!). Tony Ridder [top picture], who drove his family-founded chain into the ground, is

reported in the

San Jose Mercury News (another KR paper destroyed by his management and now also up for sale) to be distraught. I weep for him.

Background: When I was hired by the

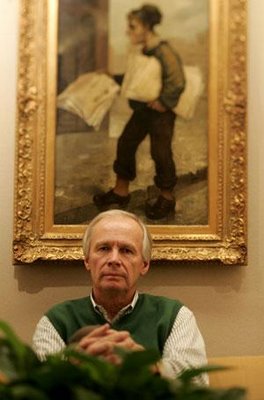

Inquirer, Knight Newspapers, owned by the illustrious Knight family, had just bought it from Walter Annenberg, who ran a thoroughly dishonest newspaper. They brought in a man named John McMullen to clean house and turn it into an honest and fearless paper, which he did. The day of my job interview I had to pick my way through a picket line of Philadelphia policemen who were protesting a series of stories on police corruption. McMullen bragged about the number of libel suits he had pending, all but one of which, incidentally, he won. Sounded like my kind of place. I was hired. The Knights eventually merged with the Ridder chain of California, forming KR. Along the way, Gene Roberts [left, bottom], late of the

New York Times, was brought in to run the Inky and in a matter of years, turned it into a great

newspaper, probably the last great newspaper to emerge in this country. On any given day, we were simply the best. We had national correspondents and foreign bureaus, experts on any subjects (know many papers with an architect writer with a degree from Yale?), budgets that were now the stuff of dreams, and won something like 17 Pulitzers in 15 years. We just ordered champaign at the end of April, figuring it wouldn’t go to waste. The foreign correspondents, who won several of those Pulitzers, were legendary, including one Asian correspondent who allegedly had a pair of teenage female twins as housekeepers. To lure one Pulitzer winner back to Philadelphia from Rome, Roberts promised him he could cover the Phillies for a year. Richard Ben Cramer covered New York City until he went overseas. He covered the invasion of Lebanon by hailing a Tel Aviv taxi. No one else covered LA with the humor and eye of Murray Dubin. Don Bartlett and James Steele won two of those Pulitzers and should have won a third for their pioneering use of computers to analyze data for a story on the criminal justice system. They worked upstairs, were given an almost unlimited budget and were told to report downstairs whenever they had their story, any year they were ready. They were almost pathologically meticulous and never got it wrong. Don Drake, the medical writer, turned in a story or two a year, maybe, always wonderfully written and often heart-rending.

I could go anywhere I wanted to go if I could justify it on journalistic grounds, including the South Pole, and I was the first western reporter allowed into Somalia in a half dozen years to find the last naturally infected smallpox victim. I had editors who included some of the best I’ve ever known. A story I wrote with Susan Stranahan on Three Mile Island (coverage of which won another Pulitzer) was nominated by the University of Maryland as one of the 100 best newspaper stories of the 20th century. We knew while we were there we had the kind of jobs we dreamed of when we went into journalism. And, we were profitable. Sunday circulation topped 1 million.

I left to go to Stanford for various reasons and the Inky kept winning awards. Roberts sent my successor to Africa for several weeks because he thought there might be an interesting story in the endangered white rhinos. There was.

Then the suits in Miami, then KR’s headquarters, started putting the screws on Roberts’ budgets for financial reasons--profit margins weren’t high enough to suit Wall Street analysts. Roberts eventually quit, blaming the corporation for reducing the budget to the point he could no longer do the quality journalism he--and we--felt appropriate, and he just got tired of fighting them constantly. Most of the staff eventually followed. He was the first of several KR editors to quit for the same reason.

A good number of former Inky reporters and editors went on to major positions in journalism, their reputation as one of Roberts' people, assuring them the appropriate respect.

Tony Ridder, known as Darth Vader in his newsrooms, was far more interested in the price of KR stock and fearful of a takeover than he was for the quality of his product, his service to his community, or loyalty to his employees. Like other newspaper corporations, KR was under pressure from Wall Street to keep earning obscene profit margins (20% plus) and, as Roberts pointed out, the suits got together and somehow the answer to falling circulation and advertising was to give the readers less. It would be like General Motors deciding that in order to earn a profit they would take out the back seats of its cars. Budgets were cut, foreign bureaus eliminated, reporters and editors bought off or laid off and the papers are now remnants of their former selves. It, of course, didn’t work and couldn’t work. They teach this shit in business schools?

(By the way, if you want to see newspapers being destroyed before your very eyes, you are welcome to watch the

Los Angeles Times and the

Baltimore Sun, both owned by the Tribune Company in Chicago--and both formerly run by Roberts' disciples from the

Inquirer--be dismembered. McClatchy is the corporation that proves the common wisdom wrong, incidentally. They have invested in their journalism instead of cutting back, and have had more than 20 years of growing circulation. Alas, they won’t try that at the

Inquirer or the

Merc.)

Now the Inky and the

Mercury News and the St. Paul paper, are up for sale. The chance of white knights rescuing them is slim. There is Gannett, whose business plan demands mediocrity; William Dean Singleton, the anti-Christ of American journalism, and the Newspaper Guild and its supporters, who won’t win because the world doesn’t work that way any more. Good guys lose to greed every time.

An old friend, Laurie Garrett, who reported for

Newsday, a Tribune paper, was invited to give a speech before Tribune Co. stockholders after she won a Pulitzer. In her speech, she pointed out that newspapers and journalism are unique businesses. So important are they to the running of a democracy that the Founding Fathers put special protection into the Constitution, a protection that no other field of endeavor enjoys, not lawyers or stock analysts or accountants. If, she told the stockholders, you don’t care about that responsibility, please invest elsewhere. Go buy stock in a shoe company or a computer company, and leave us the hell alone to do our jobs.

No one paid the slightest attention.

Steve Lovelady, one of the editors referred to above, has an interesting take on the business

here. Also, nothing I am saying should be taken as a rap against the splendid people at the Inky now, one of whom is a former student of mine. They are in no way inferior in talent or energy to the Roberts era staff. There are just far fewer of them, they are limited in what they can cover, have smaller budgets and are working for howling incompentents, including a management that tries to explain how covering fewer things is good for business. That surely ain't the staff's fault. And yes, I read the paper regularly. David Zucchino, who worked at the Inky for 20 years and is now at the Los Angeles Times, has a good story this morning from the Inquirer newsroom. He points out the paper has 300 fewer reporters than it once had and describes the newsroom as vast but lightly populated. He, of course, should know. He works at another newspaper being run into the ground by nincompoops.

Question for discussion: is it possible that a public corporation cannot run a quality newspaper? The three best papers in the U.S. are still controlled by families. Family papers turned over to corporations (often Gannett or the Tribune Co.), immediately go downhill. Maybe the pressures on public corporations make it impossible for newspapers to function properly.

[The server has been down for several hours. We apologize][Photo of Tony Ridder from the San Jose Mercury News; photo of Gene Roberts from PBS]